Cow-Calf Corner - The Newsletter, October 2, 2021

Oklahoma Fall Roundup

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

Welcome rains fell across much of Oklahoma late last week with most areas receiving one-half to two inches of precipitation. September was exceptionally dry across the state with drought conditions building quickly. The Drought Monitor tells the story. The Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI), calculated from the D0-D4 drought categories (with a possible range of 0-500), was at a low value of 8 for Oklahoma in the week of July 6, 2021, following heavy rains in June. The DSCI remained low through most of August and had a value of 17 the week of August 24. The DSCI in the latest Drought Monitor for Oklahoma jumped to 193 the week of September 28 with 93.55 percent of the state in D0-D4 including 20.32 percent in D0 (Abnormally Dry); 49.51 percent in D1 (Moderate Drought); 21.07 percent of the state in D2 (Severe Drought); and 2.65 percent in D3 (Extreme Drought). These values do not reflect the rains last week.

The latest USDA Crop Progress report showed that winter wheat planting was at 28 percent the last week of September, equal to the 2016-2020 average for the date. Wheat emergence was at 5 percent, slightly above the 5-year average of 3 percent for the end of September. Although the numbers are about average, general indications are that wheat pasture prospects are limited at this time. Some producers have “dusted in” wheat into dry soil, which will germinate quickly with the recent rains. Pockets of heavy rain may have crusted over fields with ungerminated or very small wheat and may require replanting.

Pasture conditions deteriorated rapidly in September. Range and pasture in good to excellent condition dropped from 58 percent at the end of August to 32 percent in late September. The percent of pastures in poor and very poor condition increased from 14 percent to 21 percent over the month. In the August Crop Production report, USDA forecasted 2021 Other Hay production in Oklahoma to be 8.3 percent higher year over year, an increase of 2.5 percent over the 2015-2019 average. The rapid decline in forage conditions in September may reduce that estimate somewhat. Alfalfa Hay, used primarily as a cash crop in Oklahoma, was forecast to decrease 15.8 percent year over year.

Auction prices for Oklahoma feeder cattle dropped last week reflecting seasonal price pressure and the deteriorating forage conditions. The rains late last week may help support prices some but the seasonal pressure of fall calf marketings will build in the coming weeks with the lowest seasonal price for calves expected in late October and early November. Heavy feeder cattle (over 700 pounds) typically do not drop seasonally in October and November. Feeder cattle prices are currently averaging about 8 percent higher compared to this time one year ago. Cull cow prices are also 8-9 percent higher year over year but are likewise showing seasonal pressure. On average, cull cow prices drop sharply through October to seasonal lows in November.

Management Practices for Cows at Weaning: Part 4 – Milk and Energy Balance

David Lalman and Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Department of Animal and Food Sciences Extension

This week, we continue to consider the information gathered on the cowherd at weaning. Particularly the impact of the cowherd’s milk potential on energy requirements. This week, Beef cows are resilient animals. They are programmed to adjust in real time to the environment that they experience. Some cows respond better than others and this is often referred to as "adaptability".

The early lactation period represents the most energetically expensive phase of the annual production cycle. For perspective, during the last trimester, a 1,300 lb. cow in good body condition requires about 12.7 megacalories of net energy for maintenance (Mcal NEm)to support her pregnancy and maintain her own body weight. Compare that to the same cow producing 24 lb of milk during peak lactation at 19.3 Mcal NEm per day. Interestingly, we have one set of spring-calving cows here at OSU that typically give 30 pounds of milk at peak lactation.

Consider that each one kg of milk contains about 0.33 Mcal NEm. For perspective, grass hay at 56% TDN contains 0.54 Mcal NEm per pound (dry matter basis) and lush spring forage at 68% TDN contains 0.71 Mcal NEm per pound of dry matter. Therefore, if the genetic capacity for milk production was increased from 24 pounds to 25 pounds, the cow would need to consume about 0.6 pounds more low-quality forage or 0.46 more pounds high-quality forage to keep from losing weight. While the relationship between milk yield and forage intake in beef cows is not well understood, our recent work suggests that for each one more pound increase in milk production, low-quality forage intake increases by around 0.25 pounds and high-quality forage intake increases by around .35 pounds. This is likely due to the limited capacity of the rumen. Cows can only eat so much forage in a day. When they are already consuming forage at capacity, increased energy requirements will be difficult to meet unless the energy concentration in the diet is increased.

With 0.2 pounds increase in hay intake, only an additional 0.14 Mcal NEm is available to offset the increased energy requirement of 0.33 Mcal for the additional pound of milk. The mismatch is not quite as dramatic with the lush forage because daily energy intake can be increased by about 0.25 Mcal (0.35 * 0.71).

Perhaps the take-home message is that genetic potential for milk production needs to be matched to the forage system. Research has clearly documented that excessive genetic potential for milk production can lead to cows that are thin at the time of weaning. Excessive genetic capacity for milk production and extended periods of time when forage quality is moderate to low during laction leads to negative energy balance that has to be made up at some point. Either that or increased supplementation of more energy-dense feeds will be required to close the gap between energy requirements and energy availability. Long-term, if cows are consistenly too thin (or open) year after year at weaning time, a selection program designed to lower the genetic potentioal for milk should be considered.

Making Money in the Cattle Business: Part 3 – “Put Gain on ‘em Cheap”

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Nutrition Specialist

My last two articles introduced the wisdom of my dad’s Uncle Ed about making money in the cattle business…“Buy low, sell high, keep ‘em alive, and put gain on ‘em cheap”.

So far, I have covered “Buy low, sell high” and “keep ‘em alive”, which is often difficult to do, because deeply discounted cattle are often a challenge to keep healthy and alive.

How do we put gain on cattle cheaply? Does it mean we limit spending on all inputs? Or does it mean we optimize spending to get our costs of gain as low as possible?

One of the cheapest resources to put weight on calves is perennial pasture. Budgets from research on fertilized warm-season grass pastures estimated costs to be $100/acre without supplementation, costs increased to $150/acre when byproduct supplements were fed to calves. In comparison, wheat pasture cost an average of $250/acre. Gains of un-supplemented calves on warm-season grass pasture were 1.1 lbs/day with supplementation increasing gains to 1.8 lbs/day, while calves on wheat pasture gained 2.25 lbs/day. If we are trying to minimize our total expenses it appears that grazing calves on warm-season pasture without supplementation is the way to go. But even with the higher cost of production per acre, supplementation of calves on pasture and grazing calves on wheat pasture resulted in costs of gain that were about half that ($0.50/lb) of un-supplemented calves on pasture ($1.00/lb), which translated to net return per acre of $55 for supplemented calves grazing permanent pasture and $70/acre for calves on wheat pasture compared with $30/acre for un-supplemented calves.

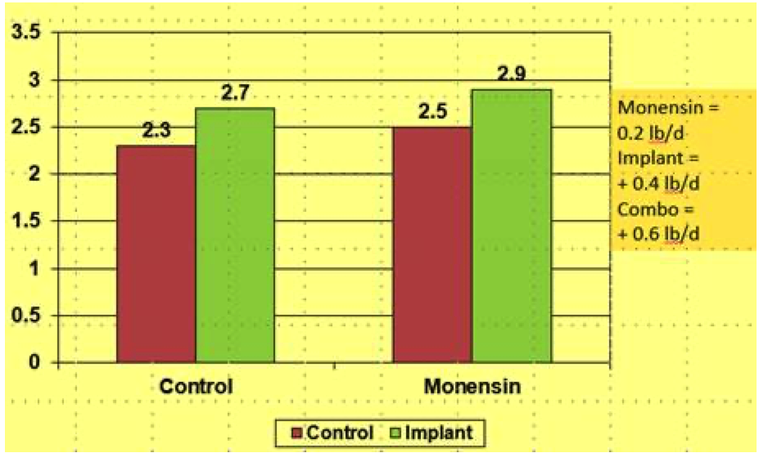

I calculated that a 10% change in performance (from 2 pounds per day to 2.2 pounds per day or by 30 pounds over a 150-day grazing period) can change net returns by around $25/head, while a 10% change in cost of gain (from $0.50/pound to $0.55/pound) can change net returns by $15/head. We can easily get an extra 0.2 pounds per day using common growth promoting technologies. Below are the results from an experiment conducted on wheat pasture where the ionophore monensin was fed in a free-choice mineral to calves that were given a growth promoting implant or remained un-implanted. Monensin increased performance of un-implanted and un-implanted calves by 0.2 lbs/day. The implant increased calves’ gains by 0.4 lbs/day. Both feeding monensin and implanting together increased gains by a total of 0.6 lbs/day. The increased gains from monensin increased net returns by $20/head, implanting increased net returns by $24/head, and both technologies together increased net returns by $42/head.

As we discussed last week, health issues will impact performance. When we evaluated the health records of multiple load lots of calves coming through stocker research facilities in Oklahoma, Arkansas and Mississippi, we found these impacts to be long reaching. Calves that were untreated or treated once for respiratory diseased gained over 2 lbs/day, calves treated twice for respiratory disease gained 1.75 lbs/day, while calves treated 3-times gained 1.65 lbs/day. Also, calves treated 2 or more times had lower hot carcass weights and took more days on feed to finish. This reduced performance will result in increased cost of gain and reduced profitability.

When we hear we make money in the cattle business by “Buying Low and Selling High”, “Keep ‘em Alive”, and “Put Gain on ‘em Cheap” we often think “that’s simple, everyone knows that”! It really may not be that easy. There is art in identifying and purchasing undervalued calves that are the “upgrading type of cattle” Uncle Ed talked about; art and skill in keeping ‘mismanaged cattle’ healthy and alive; and skill in getting calves to perform with the lowest cost of gains. But these are goals to strive for and may take a lifetime to get the formula right.